The EastFruit team recognized weather disasters as the main event in the fruit and vegetable business of Uzbekistan in 2021. A comprehensive description of the TOP-10 events is available here: part 1, part 2.

In this material, we will provide you with a detailed analysis of how frosts affected the prices for fruits, nuts and vegetables in Uzbekistan in 2021, as well as their exports. The following fruits and nuts are reviewed here: apricot, apple, pear, cherry, peach, nectarine, plum, persimmon, almond, walnut, pistachio and table grapes.

The production volumes of many key fruits for Uzbekistan, especially of early varieties, have sharply decreased due to frost. Their prices in 2021 were also high, which affected the volume of both exports and domestic consumption.

As EastFruit analysts forecasted, the apricot crop suffered the most from frosts. During the mass harvest season in 2021, the average wholesale prices for apricots increased 6-7 times and ranged from 13 000 to 40 000 UZS/kg (from $1.2 to $3.8/kg), while in the same period in 2019-2020 average wholesale prices ranged from 2 000 to 6 000 UZS/kg (from $0.2 to $0.6).

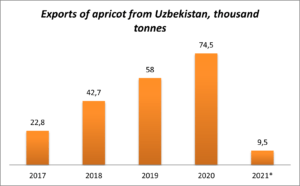

With such prices and volumes available for exports, the exports volume of apricots has sharply decreased. Exports in physical terms amounted to only 9.5 thousand tonnes in 2021, having decreased by almost 6 times compared to 2020, and turned out to be the lowest exports volume in 5 years. Prior to that, Uzbekistan was actively increasing the exports of apricot, and became the second largest apricot exporter in the world in 2020, second only to Spain.

Further, the list of “victims” was continued by apple, pear, peach/nectarine, plum, persimmon, cherry, walnuts, pistachios and almonds.

Apple: in the third decade of June 2021 – in the midst of the harvest season for early apple varieties, their average wholesale prices were at least 2.5 times higher than in the 2020 and 2019 seasons. In the past few years, Uzbekistan has been searching for an export niche for early apples in more northern countries, primarily in Russia. However, there was no question of exporting at such high prices. Another factor was the unexpected drop in apple prices in Russia in the summer, as stocks in most countries of the region turned out to be record high, and even Turkey and Iran have increased apple supplies dramatically. At the same time, many seem to have forgotten that the demand for apples in summer in Russia always sharply decreases, because of seasonal berries, fruits and vegetables available on the market.

Fortunately, the early apple harvest was unusually low in Uzbekistan. At the end of June 2021, EastFruit experts forecasted a sharp decline in the exports of “summer” apples in 2021 compared to previous years. Later, the statistics on foreign trade confirmed this: the volume of apple exports from Uzbekistan from May to July 2021 amounted to 6 thousand tonnes, having decreased 2.8 times compared to 2020 and being the lowest in the last 5 years.

As for mid and late-ripening apple varieties, EastFruit published an article at the end of their mass harvest season – at the end of September 2021, covering the effect of frost on the apple harvest in different regions of the country. Weather anomalies had a severe negative impact on the apple harvest in Uzbekistan. Average wholesale apple prices in 2021 were at least a third higher than in the 2020 and 2019 seasons.

Pear: The pear harvest was more affected by early frosts than the apple harvest. The average wholesale price for pears was 22 000 UZS/kg ($2.1) even at the end of the harvest season for late-ripening varieties at the end of October 2021, which is 38% higher than on the same date in 2020 and 3 times higher than in 2019. From the beginning of November to December 25, 2021, wholesale prices for pears increased by another 14%, updating all records.

Although Uzbekistan is a net importer of pears, it exported 1 thousand tonnes of pears worth $1.1 million from June to September of last 2020. Due to the low harvest and high prices for pears, the volume of exports fell almost 3 times in physical terms, and exports earnings – 4.5 times in the same period in 2021.

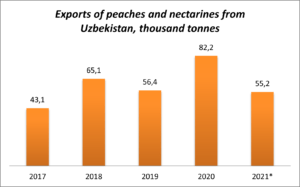

Peach/Nectarine: In the 2021 season, their average wholesale prices were 2.5-3 times higher than in 2020 and 2019. Exports of peaches and nectarines amounted to 55.2 thousand tonnes in 2021, having decreased by 36% compared to 2020. Notably, Uzbekistan exported 82.2 thousand tonnes of peaches and nectarines in 2020, ranking 5th among their largest exporters in the world.

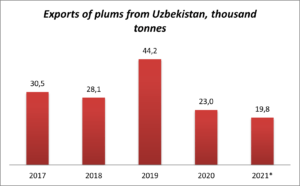

Plum: Average wholesale prices for plums in Uzbekistan during most of the 2021 season were about 3 times higher compared to the 2020 and 2019 seasons. In addition, the season was abnormally short in 2021 – there were no longer any plums offered on the wholesale markets in the second decade of September, whereas in 2020 plums were available on the market until mid-November.

Despite high prices and a short season, exports of fresh plums fell by only 14% in physical terms compared to 2020. At the same time, the exports have been declining for the second year in a row, indicating that the relatively low harvest in the 2021 season is not the only reason for the decline in exports in the final year. Moreover, the volume of exports of plums in physical terms in 2020 and 2021 was even lower than in 2017 and 2018. With the exception of 2019, there has been a steady downward trend in the dynamics of plum exports from Uzbekistan over the past 5 years.

Persimmon: After declining persimmon exports for two years in a row in 2018 and 2019, Uzbekistan exported a record volume of persimmon in 2020 and even entered the Top-4 largest exporters of persimmons in the world. However, the peak harvest of persimmons in 2021 started 10 days later than usual and the 2021 harvest was lower than in 2020 due to weather anomalies. In addition, the purchase prices of exporters from farmers in 2021 were higher than last year: they were about 30% higher at the beginning of October 2021, and by mid-October, they were already 70% higher than in 2020.

The season for exporting persimmons from Uzbekistan starts in the third decade of August and ends in the second half of January next year, but the peak accounting for about 98% of the total exports volume lasts from September to December inclusive. According to the Customs Committee of Uzbekistan, the export of Uzbek persimmon in physical terms reached 74 thousand tonnes from the beginning of August to December 25, 2021, which is 23% less than in the same period in 2020.

Obviously, the decline in the harvest of persimmons in Spain allowed Uzbekistan to get a higher price for its fruits when exported, but the harvest in Uzbekistan turned out to be lower than expected. Thus, local consumers also had to pay more for this traditional fruit, and its consumption in Uzbekistan has apparently decreased.

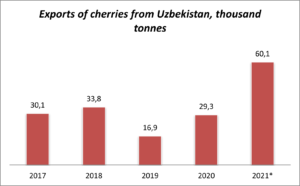

The cherry harvest was less affected by weather anomalies compared to other stone fruits. More precisely, it was the early varieties of cherries that were affected, as well as the harvest in those regions that supply cherries earlier than others.

Therefore, cherries became available in large volumes on the market and their mass harvesting in the 2021 season started 7-10 days later than last year, with rather high prices. At the beginning of the harvest season, average wholesale prices for cherries were 1.5-2 times higher than last year, depending on the caliber. Prices began to decline sharply as the harvest season entered a peak phase, and by its end, average wholesale prices were already 10-25% lower than last year, depending on the caliber. Moreover, the rate of decline in prices for large-caliber cherries was higher than for small ones.

In the article “Uzbekistan: the best cherries are exported cheap, and small cherries are expensive for the domestic market,” EastFruit analysts explained why prices for more valuable cherries that are suitable for exports declined much faster than those for smaller cherries.

Nevertheless, cherry became the only product among stone fruits, the export volume of which Uzbekistan sharply increased in 2021, and exports doubled to 60.1 thousand tonnes in physical terms (worth $83.1 million) against 29.3 thousand tonnes (worth $56.4 million) in 2020. This was a record volume of cherries exported from Uzbekistan ever. However, the price was close to the anti-record.

Walnut: the harvesting of walnuts in Uzbekistan starts in early September, and EastFruit analysts made preliminary estimates of damage from weather anomalies to the walnut harvest based on interviews with farmers in mid-September 2021. According to producers, frost damage to the walnut harvest ranged from 5% to 50%, depending on the region. On average, Uzbek farmers received less than 20-30% of the walnut harvest.

At the end of the season of mass harvesting of walnuts, the average wholesale prices for inshell walnuts were 30-40% higher than last year.

Despite relatively high prices, exports of walnuts of the 2021 harvest increased. According to preliminary data, Uzbekistan exported 2.2 thousand tonnes of walnuts of the 2021 harvest worth $8.5 million from September to December 2021, which is almost 63% more in physical terms and 25% more in terms of export earnings compared to the same period in 2020.

Surprisingly, the physical volume of walnut exports from Uzbekistan increased more than the proceeds from them, while the global prices for walnuts were growing at record rates. Nevertheless, the exports price of Uzbek walnuts turned out to be lower than last year.

Pistachio: The frost damage to the pistachio harvest was much bigger than the damage to walnuts, which was reflected in its high prices. It should be reminded that pistachio mainly grows wild in the mountainous regions of Uzbekistan. However, interest in the industrial cultivation of pistachios in Uzbekistan has been steadily growing in recent years, and some very ambitious plans have been announced. Moreover, the conditions for growing pistachios in Uzbekistan are almost ideal.

Harvesting of Uzbek pistachio starts in the first decade of August and ends in the third decade of September. The average wholesale prices for pistachios were 160 000 UZS/kg at the end of the harvest season, i.e. at the end of September and the beginning of October 2021, which is 60% higher than in the same period in 2020 and 2019. Wholesale prices for pistachios remained at this level until the end of December 2021.

You can watch how pistachio is grown in California, USA in this video.

Almonds: according to the survey of farmers in Uzbekistan by EastFruit experts after the second wave of frosts in the second half of March 2021, the possible loss of almond harvest was estimated from 30% to 90% depending on the region. As low harvest was expected, prices for almonds in Uzbekistan literally skyrocketed. From late March to mid-June 2021, the average wholesale price for inshell almonds doubled – from 50 000 UZS/kg to 100 000 UZS/kg (from $4.8 to $9.4), which is about 80% higher than on the same date in 2020. Prices remained at this level until the 20th of August when the new harvest of mid-season almond varieties started.

However, wholesale prices for almonds began to fall then, and a steady downward trend formed in the market. From the end of August to the end of November 2021, the average wholesale prices for inshell almonds decreased 2.5 times and reached 40 000 UZS/kg ($3.7). As a result, the average wholesale prices for almonds from the end of November to the end of December 2021 were 35% lower than in the same period in 2020.

What explains such a sharp drop in prices for almonds after serious crop losses expected and no imports of almonds to Uzbekistan?

According to the Uzbek EastFruit team, there are two reasons for this. First, the worst loss expectations were met only on early almond varieties, the harvest of which starts at the end of July. The yield of mid-season and late varieties, the harvest of which starts in the second half of August and September, respectively, was better than expected. The second reason is the expansion of almond plantations in Uzbekistan. The market began to receive almonds from new orchards this year, which have begun to bear fruit, affecting prices.

Grapes:

Weather anomalies in winter and the first two weeks of spring in Uzbekistan did not have a large impact on the grape harvest. However, the relatively low level of precipitation in spring, problems with irrigation in some areas of the central and southern regions of the country, as well as hot and dry summer, led to a decrease in grape yields in Uzbekistan in 2021.

Despite this, the volume of table grape production in 2021 was still higher than in 2020 due to the expansion of vineyard areas. Over the past four years, 52 000 hectares of new vineyards have been planted. As of early July 2021, grapes are grown in Uzbekistan on an area of 90 000 hectares. As a result, average wholesale prices for grapes in the 2021 season in Uzbekistan were about a quarter cheaper than in 2020.

No wonder that Uzbek producers and exporters faced an oversupply of table grapes on the Russian market in the midst of the export season. Moscow’s largest fruit and vegetable wholesale market, Food City, was oversaturated with grapes from Uzbekistan in late August and early September, and their prices were extremely low. This is quite natural, as the supply of grapes from competing countries such as Turkey, India, Moldova, Armenia, Iran and Azerbaijan keeps growing. Many of these countries offer more modern varieties in more modern and retail-friendly packaging.

As for the competitiveness of table grape varieties grown in Uzbekistan in foreign markets, including the possibility of opening new sales markets, the prospects for Uzbekistan are far from being promising, EastFruit analysts say. The article with a rating of the most popular varieties of table grapes in Uzbekistan published in May 2021 caused a heated discussion among winegrowers and showed that the industry needs to take urgent measures if it wants to maintain its position in this competitive market.

Uzbekistan is the largest exporter of table grapes in Central Asia and one of the Top-15 world’s largest exporters. Moreover, grapes are the main export position of Uzbekistan in the fruit and vegetable sector, especially if we take into account the exports of raisins. Unfortunately, the exports of Uzbek grapes is limited to post-Soviet countries – almost the entire export volume of Uzbek table grapes is bought by three countries: Russia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

At a meeting on the development of viticulture and industrial processing of grapes in July 2021, the head of state set the task to create new export-oriented plantations in 44 regions of Uzbekistan based on the experience of past years. To this end, it is envisaged to allocate additional subsidies and compensations from the budget, incentives for the import of equipment and technology used in viticulture, tax incentives, resources to banks to finance the planting of vineyards in the amount of $100 million, and to create new high-yielding, seedless, cold-resistant and disease-resistant grape varieties based on foreign experience.

Unfortunately, these measures can only lead to an aggravation of the surplus of grapes on the market and a further drop in prices. Uzbekistan does not need to increase the volume of grape production, but to renew plantations, laying down varieties that are more promising and demanded on the global market.

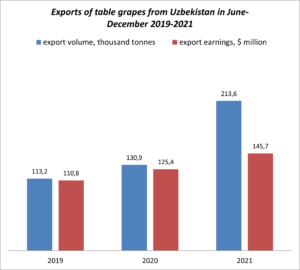

Table grapes became second after cherries in the fresh fruit segment in terms of the growth rate of export volume in physical terms in 2021. Uzbekistan exported 212.1 thousand tonnes worth $144.8 million from June to December 2021 (the season for the export of table grapes from Uzbekistan starts in the second half of June). Compared to the same period in 2020, the exports of grapes increased by 62% in physical terms and by 16% in exports earnings.

Unfortunately, such a large difference in the growth of physical volume and revenue is explained by the prices for exporting Uzbek table grapes being about 30% lower in 2021 than in 2020. If we take into account the sharp rise in the cost of logistics this year, it can be assumed that the income of winegrowers from such exports decreased even more significantly. And this is another proof that Uzbekistan should not increase the volume of grape production, but work on modernizing the entire industry: from replacing varieties to improving processing, cooling, packaging and logistics.

The use of the site materials is free if there is a direct and open for search engines hyperlink to a specific publication of the East-Fruit.com website.