EastFruit analysts draw attention to the increasing frequency of media reports about Kazakhstan’s export successes in the field of vegetables. This is somewhat surprising, because it is far from reality, and it is appropriate to say that Kazakhstan is the largest market for vegetables in Central Asia!

Most other countries in Central Asia have either large positive vegetable trade balances or balanced trade, but Kazakhstan has always been a net importer. Moreover, the negative balance of trade in vegetables in Kazakhstan has had a clear negative trend over the past few years.

Let’s figure it out. First, let’s look at what is happening in the exports of vegetables from Kazakhstan.

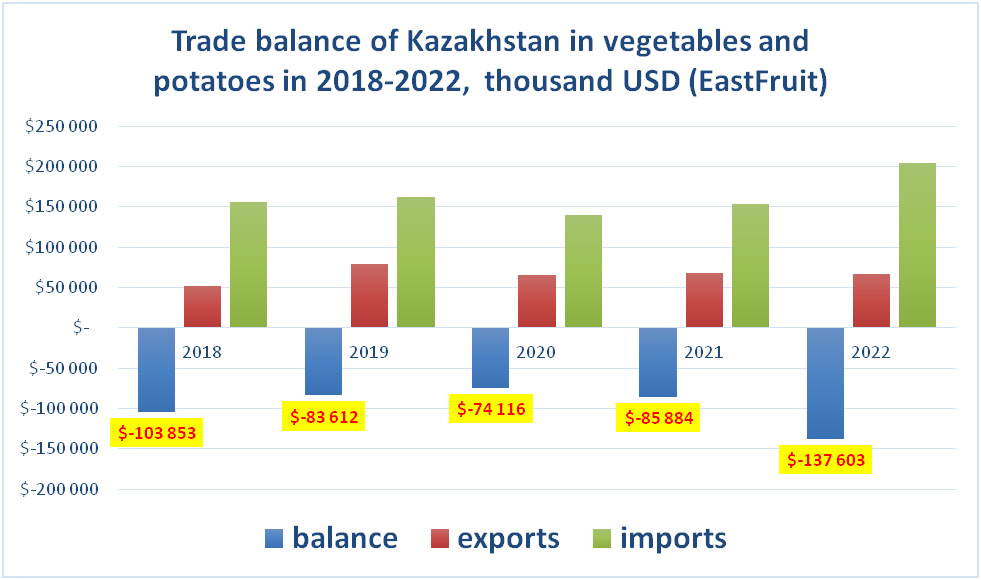

Exports of vegetables and potatoes from Kazakhstan over the past 5 years (2018-2022) have indeed had growth dynamics. On average, exports grew by 2.5% or US $1.7 million over the year and averaged US $65.8 million per year. It seems not bad, right? But wait for the information on imports!

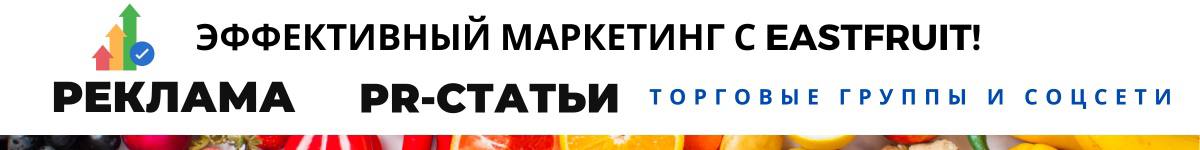

The export structure looked quite simple – three crops: potatoes, tomatoes and onions provided 77% of all export earnings.

Also among Kazakhstan’s relatively large export items are cabbage, cucumber, and carrots, although here the export volumes were relatively small in relation to the exports of the vegetables indicated on the above graph.

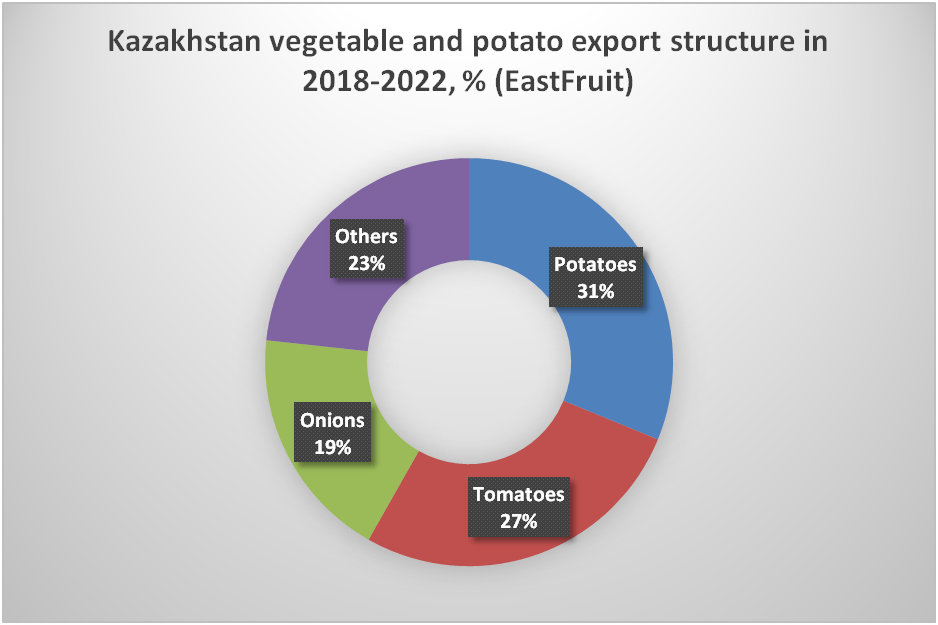

The geography of Kazakhstan’s exports of vegetables and potatoes was even simpler than the structure of exports. More than half of the products were exported to Russia and 32% to Uzbekistan. The remaining countries, among which only Turkmenistan and Belarus can be distinguished, bought very small volumes of Kazakh products.

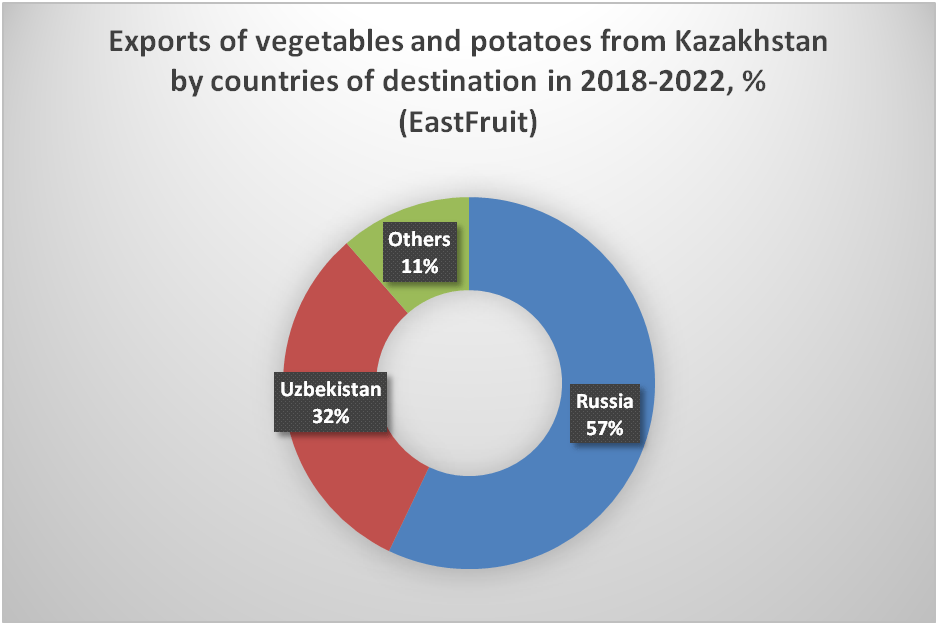

Imports of vegetables to Kazakhstan were 2.5 times higher than exports, and on average for 2018-2022 amounted to US $162.9 million per year. Moreover, the growth rate of vegetable imports was more than twice the growth rate of exports and amounted to 5.3% or US $8.7 million per year. In other words, Kazakhstan’s dependence on vegetable imports was growing rapidly.

The structure of vegetables imports to Kazakhstan was much more diverse than the structure of exports, but about half of the imports accounted for three items: tomatoes, onions and peppers.

Let’s make an interesting digression – when talking about the exports of vegetables from Kazakhstan, often the first thing that comes to mind is onions. However, onions are the second largest import item in the country. Potatoes also made it into the top 8 main import positions, which is also the main export crop in this category for Kazakhstan. And, of course, the same is true to tomatoes, which is not surprising, given the climate realities. In other words, the main export categories of Kazakhstan in this trade group were also among the main import categories.

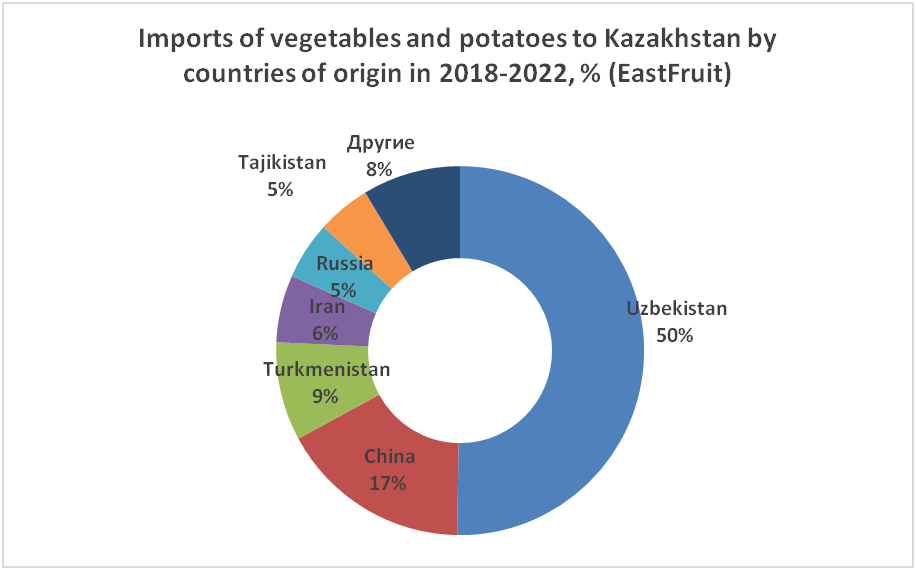

The geography of imports of vegetables and potatoes to Kazakhstan also seems very interesting. Exactly half of all imports come from one supplier – Uzbekistan. And this is not surprising, because Uzbekistan for now remains the largest exporter of vegetables in the region. We say “for now” because the incredibly rapid expansion of the greenhouse business in Turkmenistan may undermine Uzbekistan’s leadership position.

China’s second place in the imports of vegetables to Kazakhstan is also noteworthy, although a remark needs to be made here that in the recent two years, China has lost these positions to Turkmenistan and Iran. We also note that the main buyer of vegetables from Kazakhstan is also among major exporters of vegetables to this market.

Kazakhstan’s trade balance in vegetables and potatoes tends to worsen, as we already mentioned at the beginning of the article. Moreover, in 2020, when its best indicator was achieved, it was partly due to covid restrictions that prevented direct supplies of products to the Russian market from countries outside the EAEU. This allowed Kazakhstan to increase exports in the absence of competition. However, from 2020 to 2022, Kazakhstan’s negative trade balance almost doubled and exceeded US $137 million.

Uzbekistan maintains a positive trade balance in vegetables and potatoes only with Russia. However, there is a catch here – a significant part of exports to Russia from Kazakhstan is in fact the re-exports of Uzbek products. According to our estimates, the volumes of re-exports of Uzbek vegetables from Kazakhstan to Russia exceed the positive trade balance, therefore, de facto, Kazakhstan remains a net importer in this category even in its trade with Russia!

Does Kazakhstan have categories of vegetables for which this country can be considered a net exporter?

The short answer to this question is “yes” – it is true that only in potatoes, Kazakhstan has a stable positive trade balance, which amounts to about US $14 million per year. By the way, a positive balance is achieved mainly thanks to exports of potatoes to Uzbekistan- the country which is one of the world’s largest importers of ware potatoes.

In the case of onions, which Kazakhstan periodically actively exports even to the countries of the European Union, the trade balance is negative. On average, Kazakhstan imports 70% more onions per year than it exports to the foreign markets. Therefore, Kazakhstan is a large net importer of onions and the largest market for this type of vegetables in Central Asia.

Well, the trade balance for tomatoes, which ranks second among the main export categories of Kazakhstan, is even more negative. Here, imports exceeded exports by 2.5 times on average over the last 5 years, but in the near future the situation in this category will begin to deteriorate sharply, given the expansion of Turkmenistan mentioned above.

Conclusions

There is, of course, nothing wrong with the fact that Kazakhstan is a net importer of vegetables. Moreover, the presence of large volumes of re-exports is positive for the country’s economy, which allows local trading companies to create added value in Kazakhstan. In other words, Kazakhstan is becoming the largest trade hub for the vegetable and potato trade in the region.

At the same time, the constant calls for increased subsidies for vegetable and potato production in this country against this background look somewhat strange and not entirely efficient. After all, subsidizing cultivation does not increase, but, on the contrary, reduces the competitiveness of the industry and its sustainability.

Another point that can be considered negative for Kazakhstan is the high level of dependence of trade on one market only, which is in fact the most unreliable market in the region. In the ranking of the worst trading partners, Russia took a confident first place, and this country is the main buyer of vegetables from Kazakhstan, which makes investments in vegetable production in Kazakhstan a high-risk business. It is not for nothing that even Turkmenistan is now actively trying to diversify exports of its greenhouse vegetables, fearing problems with demand for them in Russia or unpredictable changes in trade relations and the exchange rate of the local currency.

Accordingly, to increase the sustainability of the vegetable and potato business, Kazakhstan should consider the possibilities of diversifying exports, liberalizing the conditions for growing and trading fruits and vegetables, and improving logistics and infrastructure for fresh produce in the country.

The use of the site materials is free if there is a direct and open for search engines hyperlink to a specific publication of the East-Fruit.com website.